Metropolitan News-Enterprise

Friday,

June 10, 2005

Page

7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

LACBA’s Republican Caucus Makes Endorsements

By

ROGER M. GRACE

What

would you think of the idea of Republican members of the Los Angeles County Bar

Assn. banding together and issuing endorsements of judicial candidates?

Preposterous? Conducive

to a politicizing of judicial races? Something that could never happen?

Well, believe it or not,

it’s happened. ...But a long time ago.

It’s the fascination of

the past that draws people to “paper fairs” featuring “ephemera”—printed matter

nobody would have expected at the time it was generated to have anything other

than momentary significance. Last Saturday, just as my wife and I were about to

depart such an event at the Elk’s Lodge in Pasadena,

I spotted in a $1 tray at one of the booths a yellowing 8½x11 sheet headed:

“AS TO CANDIDATES FOR ASSOCIATE JUSTICE SUPREME COURT.”

The text began:

“At a meeting of the

Republican members of the Los Angeles Bar, held on the 28th day of October,

1902, the following address was, by resolution, unanimously adopted and

authorized to be published:

“The Republican members

of the Los Angeles Bar desire to present to their fellow citizens of the state

a brief statement concerning the Hon. Lucien Shaw, and his qualifications for

the high office of Justice of the Supreme Court to which he was nominated by

the recent Republican State Convention.”

|

|

|

|

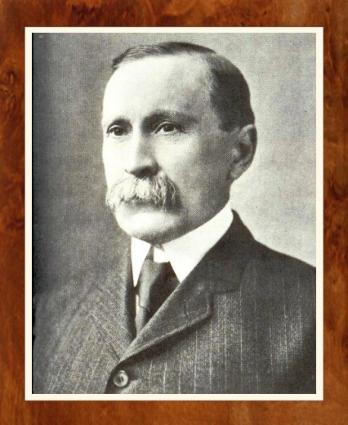

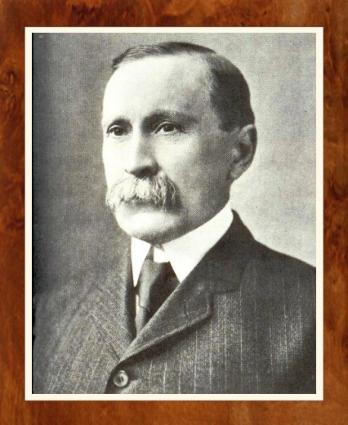

LUCIEN SHAW

1845-1933 |

|

“Believing

that Judge [Frank M.] Angellotti’s well known ability and long and meritorious

service on the [Marin] Superior Court Bench should be recognized and rewarded,

we also heartily endorse his candidacy for Associate Justice of the Supreme

Court.”

Among

those signing the statement was E.A. Meserve, who in 1889 founded what is now

known as Meserve, Mumper & Hughes LLP, one of the oldest law firms in California.

In case you had any

doubts, I did pay the dollar to obtain a copy of what amounts to a press

release, but a historical one reflecting that long-ago time in our state’s

history when judges were partisan politicos.

During

a talk before the Culver-Marina Bar Assn.

early in 2000, I had occasion to comment: “Remember, you heard it here first.

George W. Bush is nominated at the Republican convention, and is defeated in

the fall election.” That was not, I quickly added, a prognostication of the

outcome of the presidential contest that year, but a recitation of the facts in

the case of Bush v. Head, decided

by the California Supreme Court in 1908.

The case illustrates the

mischief that can be spawned by the nomination of judicial candidates by

political conventions.

In 1902, Charles M. Head

was elected as judge of the Superior Court in Shasta, then a one-judge county.

The Legislature in 1905 created a second judgeship for the county, which irked

Head. Gov. George Pardee appointed Bush to the temporary vacancy, to be filled

by voters in 1906. The Republican Party nominated Bush as its candidate for the

post.

The Democratic Party

nominated Head—whose existing term of office was not set to expire until

January, 1909. Head promised the Democrats that if they nominated him, he

would, if elected, decline to take the oath of office, thereby restoring the

county to its one-judge status.

And voters, knowing of

that pledge, elected Head in order to save tax money.

The upshot of the

opinion was that Bush could maintain an election contest. Not reflected in the

opinion was that Bush, in the meantime, had been appointed by Gov. James N.

Gillett to the vacancy created when Head failed to take the oath of office.

That 1906 election was

the last one in which judicial candidates were nominated at political

conventions. The Legislature in 1909 enacted the Wright-Stanton bill, creating

direct primary elections. However, judges were still nominated by political

parties in the 1910 election.

Few

would advocate a return to partisan elections

for judgeships, the last such elections having been held in 1910. (Retention

elections for appellate justices, another reform seemingly without detractors,

came in 1934.)

It seems basic to us

today that a judge who is included on a political party’s ticket is necessarily

committed to the party’s platform while the only commitment a judge should have

is to the law.

Yet, back in 1910, when

the reform-minded Hiram Johnson was running for governor as the Republican

nominee, his proclamation on Oct. 14 during a speech in Berkeley that “[w]e

believe in a nonpartisan judiciary” drew fire. The Oakland Tribune, in an

editorial appearing the following day, recited that “Mr. Johnson is not running

on a non-partisan ticket,” and pointed out that the Republican judicial

candidates “were nominated, as he was nominated, as candidates of the

Republican party.”

The newspaper remarked:

“An appeal for a

non-partisan judiciary voiced by the head of the Republican ticket can be

construed as in the nature of advice to Republican voters to bolt their own

judicial nominees in favor of Democratic candidates. Probably Mr. Johnson did

not intend to give any such advice, but nevertheless his remarks admit of that

construction. They were therefore unfortunate and calculated to disturb

Republican harmony. For when party voters begin cutting their ticket they are

not likely to stop at one man.”

In his inaugural address

on Jan. 3, 1911, Governor Johnson repeated his call for a “non-partisan

judiciary,” proposing:

“[W]hen upon the ballot

the title of the judiciary is reached, the names of all the candidates may be

printed without any party designation following those names; and in this

fashion all of the candidates for judicial position will be presented to the

people with nothing to indicate the political parties with which they have been

affiliated.”

In his second inaugural

address, on Jan. 5, 1915, Johnson recited advancements that had taken place

during his first term. He was able to note that “election of judges, school

officials, and county officers has been made non-partisan.”

An editorial in the Reno

Evening Gazette on Oct. 9, 1912 urged that Nevada

follow California’s

example in ending partisan judicial elections. It observed that “[b]efore California

adopted the non-partisan judiciary system,” there existed “the nefarious method

of juggling with judges to satisfy varying moods of machine bosses.”

Shaw

and Angellotti, the judges endorsed

for the Supreme Court in 1902 by LACBA’s GOP division, were elected to 12-year

terms. When they came up for reelection, it was the first year of nonpartisan

balloting for justices of the Supreme Court. Angellotti ran for the post of

chief justice that year and Shaw ran again for the office of associate justice.

There were two associate

justice seats up for election on the Supreme Court that year and four

candidates. The names of all four appeared bunched together; William P. Lawlor

and Shaw drew the highest number of votes, each gaining election.

That sort of system (akin

to that used now for electing members of parties’ central committees) has long

struck me as one well suited to trial court elections.

Election after election,

there are two outstanding candidates running for the same open seat and two

less than stellar contenders vying for another open seat. In fact, in 1986, we

had a choice between two candidates for the Los Angeles Municipal Court seat,

incumbent David Kennick and challenger Robert Furey, judge of the Catalina

Justice Court. Both were branded “not

qualified” by the County Bar and were facing Commission on Judicial Performance

charges (subsequently being ordered removed from office).

If there were five open

seats and 14 candidates in a primary election, it would make sense to stick the

names of all 14 candidates under the heading “Judges, Superior Court,” allow

the voter to make five selections, and award the seats to the five top

vote-getters. At least theoretically, this would result in the five best

qualified candidates being elected. In practice, given that there’s a great

deal of uninformed vote-casting in judicial elections, there would still be

some voter blunders, but it would end the scenario of having to choose between

a Kennick or a Furey or between two candidates with impressive credentials.

Too, it would eliminate elections for open seats in the general election, this

cutting the oppressively high costs of running for a judgeship.

I don’t

suppose that notion will attract

any more favorable response than my suggestion a few years ago of restricting

voting in judicial races to that group that has the most interest in those

races and the relevant knowledge: lawyers and judges. Allowing the lay public

to vote for judges—often relying on advice from their lawyers or listings on

slate mailers which they think are endorsements, not knowing that candidates

pay to get on those slates—strikes me as inane. After all, we don’t have

popular elections of the surgeon general of the United

States or chiefs of staff of

publicly funded hospitals, or presidents of state colleges; the public simply

does not have informed bases for making such selections.

Elections of judges

could be held in conjunction with balloting for the State Bar Board of Governors,

with judges, whose bar membership is temporarily in limbo, being enfranchised

with respect to judicial contests.

I’ve been told that this

offends the precept of egalitarianism. That objection, I would suggest, is far

outweighed by another policy consideration. My proposal would achieve a further

depoliticization of judicial elections. That’s a cause that has advanced

greatly since the time the leaflet I procured last Saturday was printed, but

hasn’t advanced enough.

Terry Friedman was

elected as a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court in 1994. He was then a

Democratic assemblyman and moneys rolled into his coffers from surplus funds

contributed to partisan Democratic campaigns. Last year, Donna Groman attained

a Los Angeles Superior Court judgeship having run as a Democrat, boasting

endorsements from a myriad of Democrat clubs. Friedman and Groman were nearly

as much Democratic candidates as Shaw and Angellotti were Republican

candidates. The difference is that partisan election of judges was the system

in 1902; it isn’t now, but nonpartisanship can be circumvented, as it was by

Friedman and Groman.

Let’s

get back to the main subject of

the 1902 proclamation, Lucien

Shaw.

He was personally and

deeply affected by the San Francisco

earthquake of April 18, 1906. A wire service story on April 25 of that year,

emanating from Los Angeles,

reported:

“Justice Lucien Shaw of

the State Supreme Court has received advices that his wife, reported among the

missing, has been found at the Presidio in San

Francisco, safe and well. For two

days after the disaster Justice Shaw, who sped north from here on a special

train, searched San Francisco

for Mrs. Shaw, returning here, hopeless, on Sunday.”

A 1906 recitation of the

San Francisco

earthquake by Hubert D. Russell told of Shaw’s frantic search for his wife.

Russell was apparently unaware of the “happy ending” to the story, writing:

“Thursday morning at

daybreak [Shaw] reached his apartments [in San

Francisco] on Pope

street. Flames were burning

fiercely. A friend told him that his wife had fled less than fifteen minutes

before. She carried only a few articles in a hand satchel.

“For two days and nights

Judge Shaw wandered over hills and through the parks about San

Francisco seeking among the

200,000 refugees for his wife.

“During that

heart-breaking quest, according to his own words, he had ‘no sleep, little food

and less water.’ At noon

Saturday he gave up the search and hurried back to Los

Angeles, hoping to find that

she had arrived before him. He hastened to his home on West

Fourth street.

“ ‘Where’s mother?’ was

the first greeting from his son, Hartley Shaw.

“Judge Shaw sank

fainting on his own doorstep. The search for the missing woman was continued

but proved fruitless.”

After

his 1914 reelection, Shaw went on to serve as

chief justice from November of 1921 to January of 1923. He succeeded Angellotti,

who had resigned from the post he won in 1914.

Following his retirement

from the bench, Shaw became a member of the Board of Directors of the Pacific

Mutual Life Insurance Company.

He died in Glendale

on March 19, 1933, at the age of 88. He was survived by his wife, Anna, and his

son, Hartley, a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court.

The Hermosa Beach

Chamber of Commerce and Visitors Bureau lists on its website as one of the

burgh’s “points of interest” the “Justice Shaw House” at 740 The Strand. This

description is provided:

“The former home of

Supreme Court Justice Lucien Shaw, founder of the Los Angeles Bar Association.

His family is still in the legal business in Los

Angeles….”

Well, Shaw was actually

one of the principals in 1888 of reorganizing

the county bar, that group having started in 1878. Among other reorganizers was

Walter Van Dyke who, like Shaw, later became a member of the California Supreme

Court.

As long as we’re on the

subject of history: this column was launched 32 years ago tomorrow.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company